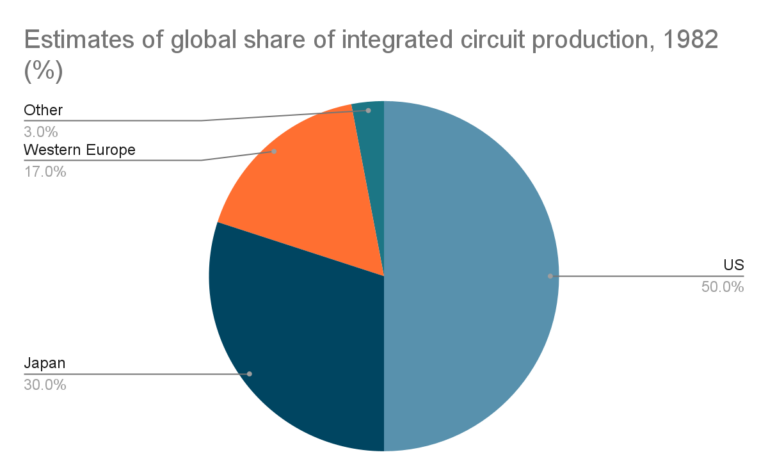

In the realm of technological advancement, the quest for hardware independence stands as a formidable challenge for the European Union (EU). Historically, the EU’s journey in semiconductor technology, marked by initiatives like the Eurochip in the 1980s, has been a tale of striving for self-reliance in a domain dominated by American and Japanese advancements. This pursuit was not merely about catching up technologically, but also about securing a position of strength in a strategically crucial sector.

The Eurochip initiative, though a bold step towards self-sufficiency, unveiled the inherent challenges in breaking free from technological dependence. Despite the ambition, Europe found itself grappling with the intricacies of vendor lock-in and a heavily entrenched private sector. The limited success of these initiatives highlighted a critical lesson: the significance of strategic public sector involvement and the necessity to foster a competitive, innovation-driven environment.

The comparison of European strategies with the successful models of Taiwan and the United States sheds light on the importance of government-led initiatives in establishing a resilient semiconductor industry. Taiwan’s state-directed approach, in particular, demonstrates the effectiveness of a coordinated strategy in fostering industrial capabilities.

Moreover, the current landscape presents renewed opportunities and challenges for the EU. The introduction of initiatives like the European Chips Act signals a fresh attempt to revitalize the semiconductor industry. However, there lies a risk of repeating historical mistakes, such as failing to implement enforceable conditions and allowing established firms to monopolize funding and influence.

For a comprehensive understanding of these challenges and strategies, a closer look at the global semiconductor industry is provided by Roy Cobb Phennomenal world

In summary, the path to hardware independence for the EU is fraught with lessons from the past and insights from global success stories. It necessitates a profound understanding of the historical context, the dynamics of global technological competition, and a bold reimagining of future strategies.

Furthermore, it is essential to note that the EU does not possess significant software platforms, such as operating systems, which further contributes to its dependency. This dependency is not limited to hardware but extends to software infrastructure as well. Given that 95% of Western communication is controlled by Meta, it’s evident that the EU faces serious challenges not only in the hardware sector but also in the areas of software and communication. This monopolistic trend in communication technologies represents an additional layer of challenge for the EU in its efforts to reduce dependence and increase technological autonomy.

Communication Security in the EU: Challenges and Implications

Communication security is another critical aspect in the discussion of the EU’s technological independence. The fact that most hardware and software are in the hands of the USA and China raises serious questions about data privacy and security. The US Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) allows the USA to monitor international activities, implying that activities within the EU are potentially subject to surveillance. This surveillance capability not only compromises the privacy of EU citizens but also poses a risk to business and government operations.

The economic impact of such a situation should not be underestimated. When business data and communications are exposed to the risk of surveillance by foreign powers, it can lead to a loss of competitive advantage, damage to consumer and partner trust, and a slowdown in economic growth. This risk is particularly pronounced in industries that depend on the protection of intellectual property and sensitive information. Thus, the issue of the EU’s technological dependency is not just a matter of economic efficiency but also a matter of national security and sovereignty.

The EU’s response to these challenges must be comprehensive. It includes the development of its own technological capacities, not only in the area of hardware but also in software, including operating systems and communication platforms. Additionally, it is necessary to establish stricter data protection and privacy standards, and to develop mechanisms that will ensure the security and integrity of communications within the EU. Through these measures, the EU can reduce its dependency on foreign technologies and increase its resilience against potential security threats.

In conclusion, it is evident that achieving technological independence and security requires strategic planning and decisive action from the EU. This involves not only investing in the development of its own technological capacities but also rethinking the structure of the global technological landscape and its impact on the economic stability and security of the EU. Only through the integration of these elements into its policy and practice can the EU hope to achieve true independence in the technology and communication sectors.